Back in June of this year, a trial-run ferry took a boatload of ferry-boosters from Wall Street to Coney Island. The folks behind this proposed new service conducted the one-time trip to demonstrate how the line would run, and to raise funds to improve the pier at Coney Island Creek where the ferries would dock.

On the way we passed barges and tugs, and crossed under the Verrazano Bridge, impressive and sometimes even sublime sights but common enough ones for New Yorkers.

What isn't commonly seen by most New Yorkers is Coney Island Creek itself.

Before I began this park odyssey, I'd been to Coney Island by subway, by car, and by bicycle. I knew you didn't have to cross a body of water to get there. So why Coney Island? Because it was an island once. And a clue to that history is Coney Island Creek, which separates the western part of the "island" from Brooklyn's Gravesend neighborhood.

The creek begins as an inlet off Gravesend Bay. As the ferry entered the inlet we saw, to our surprise, a sandy beach with a handful of people on it.

This isn't part of the famous beach at Coney Island where millions of people cavort every summer. That's along the south coast. This, by contrast, is an untended stretch of sandy land off a completely different part of the island, facing north toward "mainland" Brooklyn.

Further into the Creek we spotted a number of boats washed up and left to rot last year by Sandy, and a more historic wreck: the Yellow Submarine, hand-built by a man who wanted to use it to raise the Andrea Doria.

A man, probably wondering what a big ferryboat was doing drifting around in Coney Island Creek, serenaded us on the tuba.

The return trip saw us through a spectacular sunset. But it left us wondering what that beach was, and the grassy areas adjacent to it, and how could we get there?

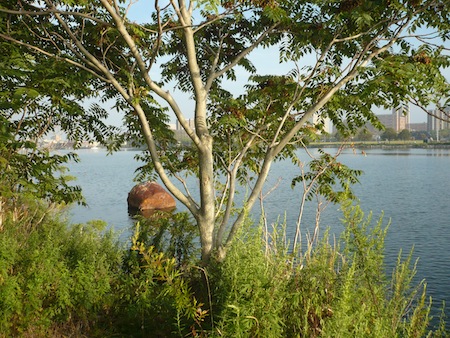

So one recent weekend we set off to find out. From the Stillwell Ave./Coney Island subway station we walked up to Neptune Ave. and headed west to where, according to the map, the creek bent south. Sure enough, water came into view after a while. At first we thought a glimpse through a gas station fence was the best we'd get.

But then we found the entrance to Kaiser Park, which is right by Mark Twain Intermediate School for the Gifted and Talented, and is named for a principal of that school back when it was more humbly known as Mark Twain Junior High School. Nearby, too, is a huge Greenthumb garden, more of a farm than a garden, with a big variety of crops growing, and even people working in the fields.

And then, as we entered the park: Payoff!

Here's the yellow submarine again, this time from shore.

I can't resist the visual fascination of once-developed or industrial but currently non-landscaped shoreline. I had to look twice to realize this was a drain.

Aside from a few people setting up to shoot a video in one of Kaiser Park's many athletic fields, the only major activity on this particular day was fishing.

A big tidal mudflat was filled in to create the 26-acre park, beneath which, according to a historical sign, "numerous shipwrecks lie." If you dug up and fixed up all the shipwrecks buried around New York City's hundreds of miles of coastline and gave them to the ancient Greeks, they could try again and really conquer Sicily this time.

At the far western end of the waterside path, an avenue of trees leads back out to the street.

Here at the western end the park per se comes to an end, but go through an opening and there it is: the mysterious beach we saw from the ferry. Untended, hardly anyone there. A father and son, a couple of lovers, a kayaker, and a guy wading way out into the middle of the cove with a fishing net.

There you have it. New York City and its parks: a place of endless endlessness and infinite discovery. Next up: Calvert Vaux Park, on the other side of the creek. Stay tuned.

As a result I came to associate great blue herons and other large, exotic birds with far-off, countrified lands where sooty cities were only a distant memory or a dream.

As a result I came to associate great blue herons and other large, exotic birds with far-off, countrified lands where sooty cities were only a distant memory or a dream.

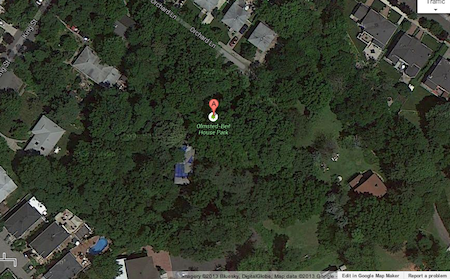

I only discovered it when exploring Coney Island Creek, which it borders to the south. My circa-1994 Five Borough street atlas calls it Dreier-Offerman Park, a $40 million renovation of which was supposed to be part of a big capital project under Mayor Bloomberg's

I only discovered it when exploring Coney Island Creek, which it borders to the south. My circa-1994 Five Borough street atlas calls it Dreier-Offerman Park, a $40 million renovation of which was supposed to be part of a big capital project under Mayor Bloomberg's