During my many years in Brooklyn I found myself in the Carroll Gardens neighborhood many times, but never visited Carroll Park.  When I headed out there on the F train the other day to correct that lapse, I was expecting more greenery. I think that's because when I think of Carroll Gardens I think of its residential blocks lined with very deep front gardens. The park, though, turns out to be mostly for active recreation.

When I headed out there on the F train the other day to correct that lapse, I was expecting more greenery. I think that's because when I think of Carroll Gardens I think of its residential blocks lined with very deep front gardens. The park, though, turns out to be mostly for active recreation.

However, between a big playground area and the ball courts is a section where you can amble around one of NYC's many World War One memorials, this one a Soldier and Sailor monument sculpted by Brooklyn-born Eugene H. Morahan and dedicated in 1921. The sad image on the side you see in the photo to the right represents a soldier grieving for his slain comrades.

Carroll Park is old – Brooklyn's third-oldest park, once a private community garden, acquired by the City of Brooklyn for the public in 1853. Who's Carroll? I never knew until now. The neighborhood, the street, and the park are named for Charles Carroll of Carrollton (1737-1832), the only Roman Catholic to have signed the Declaration of Independence and the last living signatory, dying in 1832 at age 95.

Why, I wondered, is a Brooklyn neighborhood named for a Maryland dignitary? Immediately I thought of the Maryland troops who enabled the safe escape of Washington's army in the Battle of Brooklyn, but it took a printed book (The Neighborhoods of Brooklyn) and not internet research to learn that I was right, more or less: Charles Carroll had sent that regiment.

I had speculated that the area's early-19th-century Irish settlers, feeling proud of the only Declaration signer who shared their Popery, had come up with the name, but in fact the neighborhood didn't get its name until the 1960s. Before that it was just part of "South Brooklyn," a designation that's dropped out of common use. So what was the park called before the 1960s? Readers? Anyone?

Another far-fetched association Charles Carroll had with the Borough of Brooklyn, which is also known as Kings County, is the coincidence that in the 17th century his Carroll ancestor (once "Ó Cearbhaill") emigrated to Maryland from King's County in Ireland (now County Offaly). Something else for the meaningless curious fact file.

I've drifted far from the topic of Carroll Park, but the fact is Carroll Park isn't very interesting. The coolest thing about it is the decorative cast iron gates and fencing, which date from a big 1994 restoration.

It also boasts one of the most beat-up chess tables I've seen in any park:

Oh, and a big rock someone drew a goofy face on:

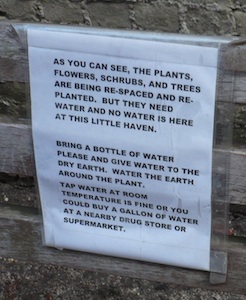

Is the rock grinning triumphantly at having killed the tree? Or was the tree a victim of Sandy? What's that big hole up the middle of the trunk? Or is there some other explanation for the rock being more emotionally accessible than the tree – which is, in its defense, dead? In any case, I had to look pretty hard for a real dose of chlorophyll and oxygen. I discovered a modest one in the little fenced-off garden area pictured to the left.

What's that big hole up the middle of the trunk? Or is there some other explanation for the rock being more emotionally accessible than the tree – which is, in its defense, dead? In any case, I had to look pretty hard for a real dose of chlorophyll and oxygen. I discovered a modest one in the little fenced-off garden area pictured to the left.

I found some more serious vegetation when I ventured out of the park and a couple of blocks down Smith St. to the Transit Garden, so named because it's on MTA property. (Its website headline: Our new shed!)

Transit Garden or no, I wasn't ready to get back on public transit right away, I needed more of a leg stretch, so I headed for another "park." Further south along Smith Street, under where the F train rises into the sky, are two abandoned, fenced off, gloomy recreation areas called St. Mary's Park and St. Mary's Playground. They look like more like movie sets for a gang war film than anything that was ever fit for children.

Across the street I spotted a sign with a truly wacky science-fiction message:

Building for the future is surely a good idea. But transforming the past? That's going to take some serious wormhole action. And obviously, they're working on just that behind the tall fence, a short block from the Gowanus Canal.

Having ventured this far, I concluded by hoofing it a few more blocks to an open but deserted playground called Admiral Triangle, which I checked out only because of its curious name. A quick internet search has not revealed an explanation for "Admiral," but this geocaching website is helpful for the other half of the name: "It is interestingly named because the park is a triangle, surrounded by trees spaced around it in a triangle, that is within a street that is also a triangle." Now you know.

The other piece (not shown) looks like a lute, and that's the one I should have photographed because I was on my way to an early music concert at the Museum of Jewish Heritage, conveniently located in Robert F. Wagner Jr. Park. Plenty of lutes – theorbos, to be exact – but no tubas.

The other piece (not shown) looks like a lute, and that's the one I should have photographed because I was on my way to an early music concert at the Museum of Jewish Heritage, conveniently located in Robert F. Wagner Jr. Park. Plenty of lutes – theorbos, to be exact – but no tubas.

When I headed out there on the F train the other day to correct that lapse, I was expecting more greenery. I think that's because when I think of Carroll Gardens I think of its residential blocks lined with very deep front gardens. The park, though, turns out to be mostly for active recreation.

When I headed out there on the F train the other day to correct that lapse, I was expecting more greenery. I think that's because when I think of Carroll Gardens I think of its residential blocks lined with very deep front gardens. The park, though, turns out to be mostly for active recreation.

What's that big hole up the middle of the trunk? Or is there some other explanation for the rock being more emotionally accessible than the tree – which is, in its defense, dead? In any case, I had to look pretty hard for a real dose of chlorophyll and oxygen. I discovered a modest one in the little fenced-off garden area pictured to the left.

What's that big hole up the middle of the trunk? Or is there some other explanation for the rock being more emotionally accessible than the tree – which is, in its defense, dead? In any case, I had to look pretty hard for a real dose of chlorophyll and oxygen. I discovered a modest one in the little fenced-off garden area pictured to the left.

appears to have been leveled by human hands in ages past and used for some purpose by Native Americans. Rediscovered during the building of the park, it was developed for rowers in the nearby Lake to explore, but not surprisingly, being a creepy hole in the ground it attracted disturbing doings. In 1929 The New York Times

appears to have been leveled by human hands in ages past and used for some purpose by Native Americans. Rediscovered during the building of the park, it was developed for rowers in the nearby Lake to explore, but not surprisingly, being a creepy hole in the ground it attracted disturbing doings. In 1929 The New York Times

a hundred times without realizing it's situated in the midst of a plaza that, by a stretchy definition, might be considered a park. Verdi Square has seating, landscaping, shrubbery, and a tree with an artificial owl in it. What more could you ask?

a hundred times without realizing it's situated in the midst of a plaza that, by a stretchy definition, might be considered a park. Verdi Square has seating, landscaping, shrubbery, and a tree with an artificial owl in it. What more could you ask? Igor Stravinsky, and Enrico Caruso. The legendary tenor, in an early example of what today we call "pre-war" real estate preferences, apparently "chose the hotel to live in because of its thick walls."

Igor Stravinsky, and Enrico Caruso. The legendary tenor, in an early example of what today we call "pre-war" real estate preferences, apparently "chose the hotel to live in because of its thick walls."

Parks Commissioner Henry J. Stern's choice of the Latin for "seventy-one" was an odd one, but I'm not complaining; the varied and the strange help make New York City the infinite wonderland that it is.

Parks Commissioner Henry J. Stern's choice of the Latin for "seventy-one" was an odd one, but I'm not complaining; the varied and the strange help make New York City the infinite wonderland that it is.